Cycling is an odd sport. Despite a few surges in the 80’s and early 2000’s it is not a mainstream option for most kids growing up. For many it is a mode of transportation you use as a child when you can’t drive or a way to get to work after your driver's license has been suspended. Bike racing is expensive. It requires a lot of insider knowledge. It is not easy to get started. And most of all, it's hard; really hard.

If you are training correctly you are, in all likelihood, perpetually hungry, tired, in some kind of pain, and ready to hurl or collapse after a workout. On top of all the general roadblocks, women's races are historically smaller and offer far less compensation than men’s fields at every level. Despite all these barriers US women have won six Olympic medals in road disciplines, compared to men’s three, since the first women’s Olympic road race in 1984.

“In 1994, while she concurrently worked a full-time job as a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, Brems (then Kurreck) won the first Women’s World Time Trial Championship. Cycling was not Brems’ first sport. ”

I started interviewing women cyclists for articles and blog posts around 2009 and was impressed with how many of them had been elite athletes in high school or college. I’m not talking about women with athletic tendencies. These women have been enmeshed in playing sports since a young age and have participated in competitive NCAA programs that were professional in all but name. They did not start their athletic careers in cycling as did Marianne Vos (Rabbobank/NED) or Coryn Rivera (UnitedHealthcare/US), prodigies who started racing when most kids were playing soccer or swimming. They came from a wide variety of sports; volleyball, rowing, soccer, running. They had found their way to cycling through injury rehab or as a way to satisfy a need to compete.

Karen Brems was one of my first interviews. While working a full-time job as a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, Brems (then Kurreck) won the first Women’s World Time Trial Championship in 1994. Cycling was not Brems’ first sport. While attending the University of Illinois from 1980-1984 Brems had competed as a gymnast. She excelled and in 1984 was named the Illinois Athlete of the year, but she was not on the Olympic track. Brems later became one of the first women cyclists to transition to cycling from collegiate athletics in the post-Title IX world.

While Title IX has not had a direct impact on cycling, the women’s peloton has benefited from a generation of athletes whose talent and skills were developed at compliant institutions. At its core Title IX is not about sports, it is about opportunity. Specifically it is aimed at providing equal access to federally funded educational programs.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

The history, controversy, and teeth behind Title IX is worth a detailed examination on its own, and if you are interested in more detail I suggest starting with the Play Fair handbook - Play Fair: A Title IX Playbook for Victory - Women's Sports Foundation.

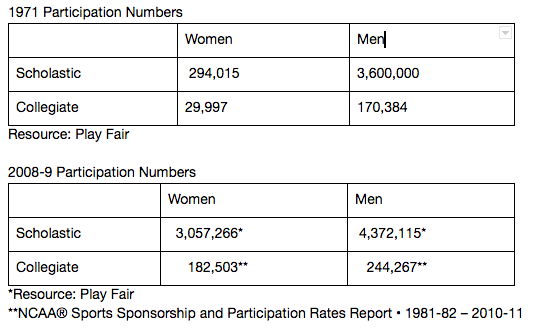

Here is a condensed version. The rules behind Title IX extend to all education programs, but athletic options for women at the high school and collegiate level were noticeable for the level of inequity. While Title IX passed in 1972, compliance did not start until the late 70s which then provided more options for women athletes. Even as enforcement began institution acceptance lagged. In the early 1980s compliance began to improve and participation numbers for women athletes rose. By 2009 participation rates were still not equal with their male counterparts but the total number of women athletes had increased dramatically.

Title IX boosted female participation in sports at the scholastic and collegiate level but where were they to go after university eligibility ended? Professional women’s sports are still in development making it difficult to dream of a career as a paid athlete. Events like the Olympics and FIFA World Cup serve as a pinnacle of achievement, and a possible avenue for generating revenue, but are primarily dependent on winning. The number of professional spots open for athletes coming out of universities is limited. A sport with a little bit of money, geographically dispersed, and a loose but growing infrastructure could go a long way. Enter bike racing.

Cycling exists in a strange netherworld in professional sports. The meaning of professional can be diced a multitude of ways. The main governing body, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), offers a 'professional' license for men but not for women. Within the men’s ranks there are several categories of professionals, everything from a WorldTour racer who commands a seven figure salary to a neo-professional making minimum wage. Some teams expect riders to bring their own sponsors and salaries, in effect, make them pay their own way. Top women's teams register with the UCI, making a UCI Women's Team the defacto 'professional' category.

“The Olympics was a big thing. Being a gymnast ever since I was a little kid I dreamed about going to the Olympics, watched it on TV and it was pretty clear pretty early that I wasn’t going to do it in gymnastics. ”

Possessing a professional license does not mean that you are able to make a living racing bicycles. A handful of women cyclists can make a decent salary but many, if not most, riders are living hand to mouth. Earning a living, or even a partial one as an athlete, requires hustle, creativity and sacrifice. Cycling, which operates on the fringe of mainstream sports, offers unending promise to those willing to give it a try. Prize money at races offers an immediate performance incentive. Existing club and team organizations offer logistical, technical and financial support. The loose format rewards talented, hungry and eager athletes. It’s a free market system with few constraints to going pro. Have you got a big set of lungs, are willing to suffer, and don’t mind the occasional broken collar bone? There is a bike race waiting for you!

Cycling went through a boom in the 80s thanks to 7-Eleven, the 1984 Olympics and Greg Lemond’s Tour de France wins. International success during this time period by pioneers like Connie Carpenter, Beth Heiden, Rebecca Twigg and Inga Thompson paved the way for the next generation of racers. Participation numbers increased and women started finding their way to the sport. In the late 80s and early 90s cycling provided a way for a handful of legendary athletes, like Laura Charameda (road racing) and Julie Furtado (first as a road racer then as a mountain biker), to compete and make a living. Women began to emerge from collegiate sports—like swimming, running, and soccer— and find their way to the races. Karen Brems was one of these athletes.

Brems graduated from Illinois and began her career as a software engineer. She moved to California and drifted into triathlons, centuries, and eventually bike racing. After college cycling helped fulfill a lifelong athletic ambition. It gave her a path to the Olympics.

“The Olympics was a big thing,” Brems said. “Being a gymnast ever since I was a little kid I dreamed about going to the Olympics, watched it on TV and it was pretty clear pretty early that I wasn't going to do it in gymnastics.

“Winning World's was a surprise to everybody, including myself, and it showed me I wasn't just making it. I wanted the medal.”

Brems’ experience would be repeated by dozens of women athletes in the coming years. Kristin Armstrong, Christine Thorburn, and Amber Neben all found their way to cycling after college, and all went on to earn World Championship medals and represent the US at the Olympics.

American cycling has been blessed by several generations of talented women looking for a home. A common thread between decades and riders is the Olympic Games. It is the marquee event for women athletes - their Tour de France, their Paris Roubaix. The Olympics is one of the few events that will draw the eyes of the entire world to their sport, but it is not without risk.

For Karen Brems, who finally made it onto the US team after her third attempt in 2000, focusing on the Olympics has a downside.

“If all you think about is the Olympics it's not enough because it's only once every four years,” Brems said. “It's so hard to make the team. There's so much that has to go right. There's politics. You have to enjoy the journey really.”