Prologue: Old Books

Prologue: Old Books

I never thought of myself as a big sports guy but somewhere along the way it became a central part of my life. I now cover professional cycling and other outdoor pursuits with a good chunk of my time. If you had asked me twenty years ago, I would have said writing about dragons would be more likely.

It is easier for me to engage in the sports world than with fiction or other types of journalism. I think it is the struggle that exists amongst teams, and between athletes. It feels like a proxy for real life in some ways. The wins and losses mean something beyond the game at stake. I never get far in figuring it out. It’s like art. So full of meaning and symbolism, it is easier to just accept than intellectualize.

That said, indulge me while I try…

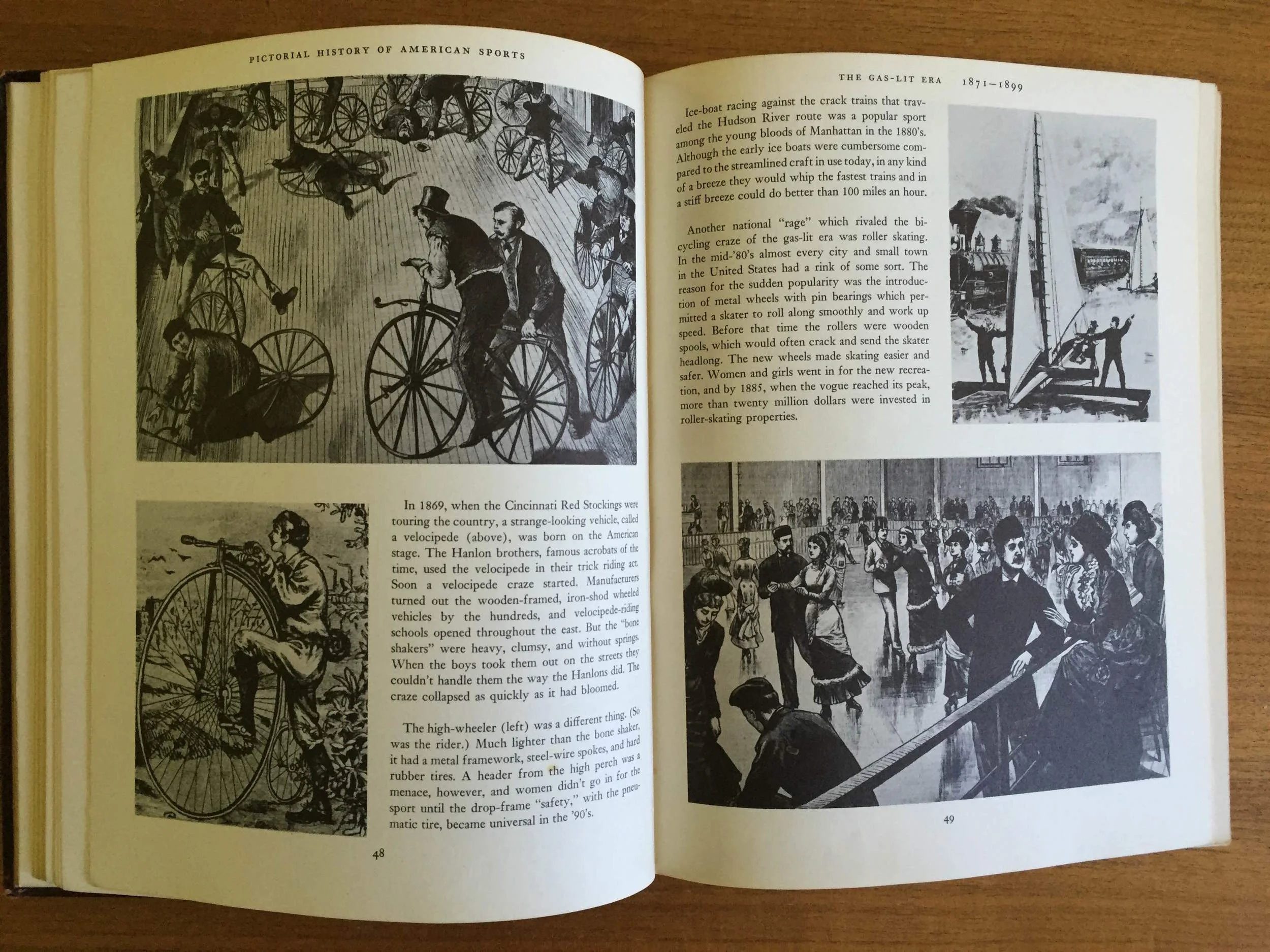

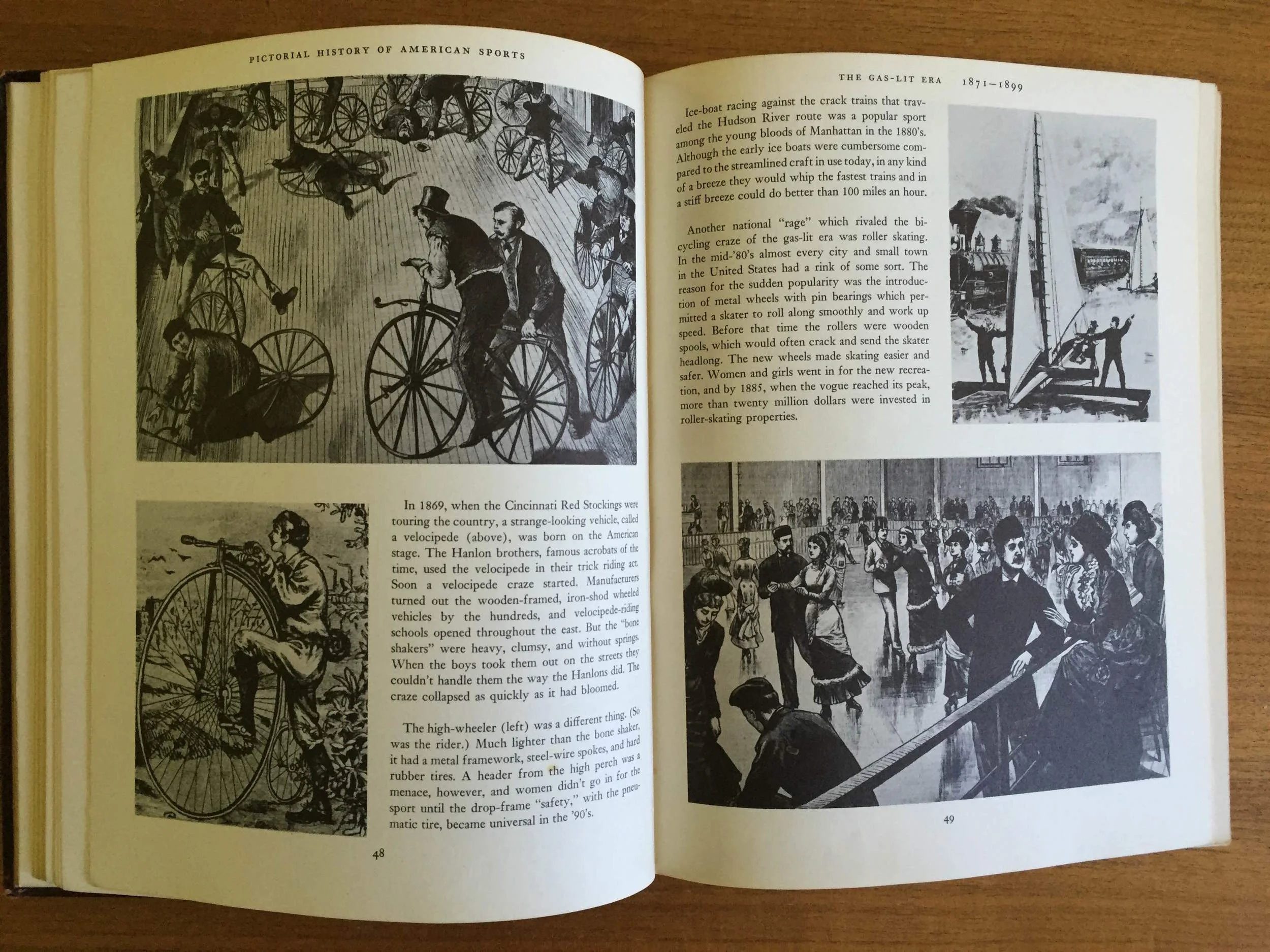

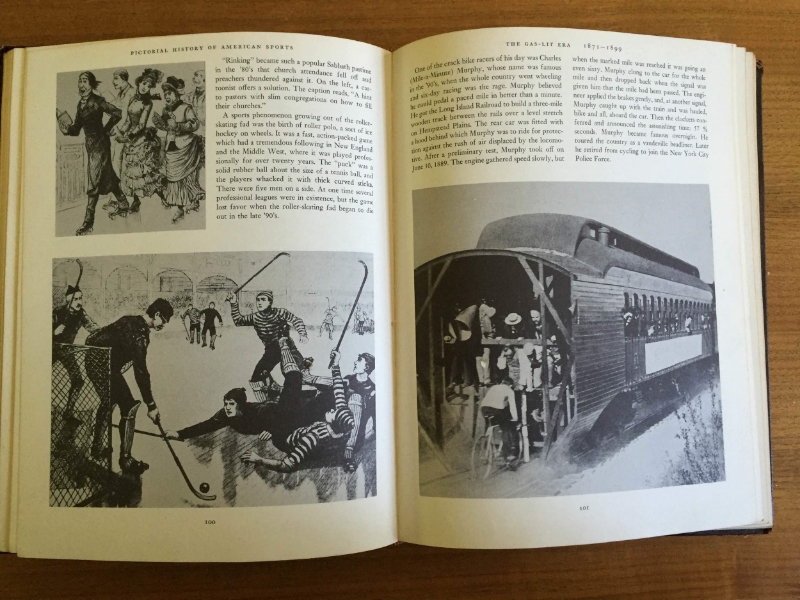

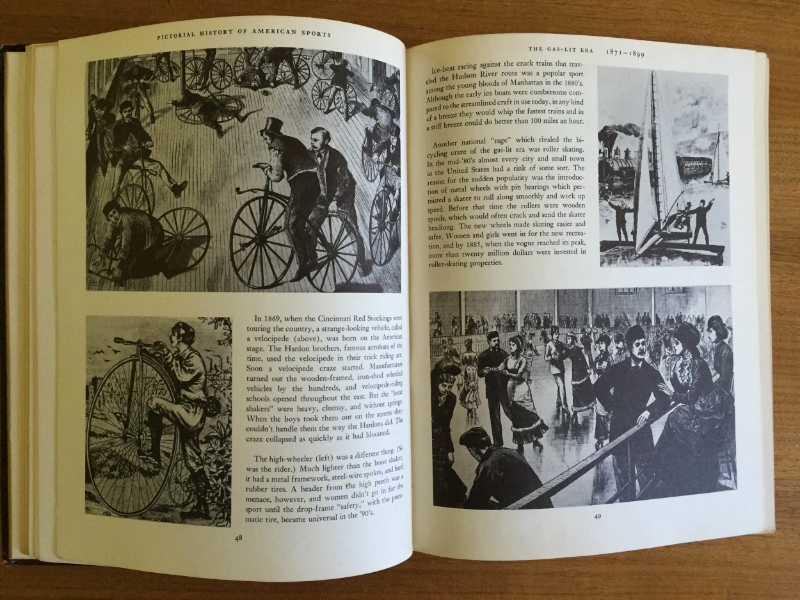

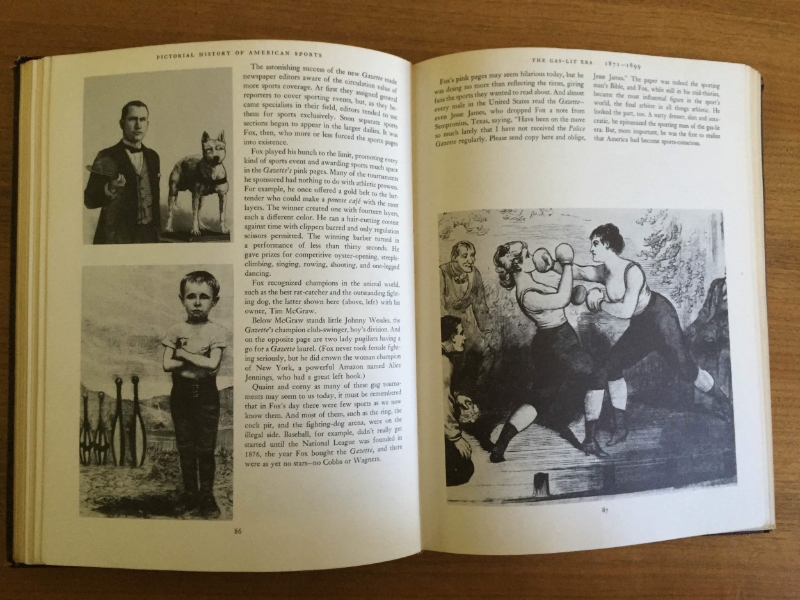

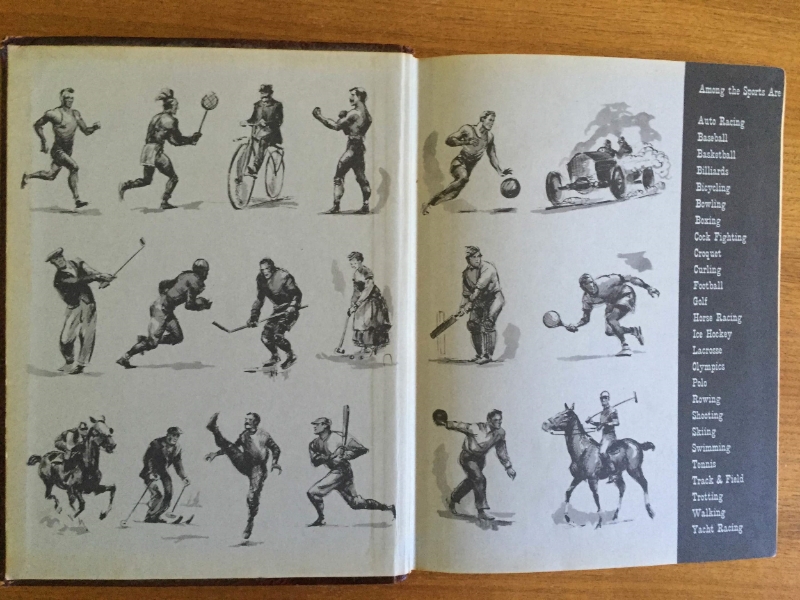

Pictorial History of American Sports

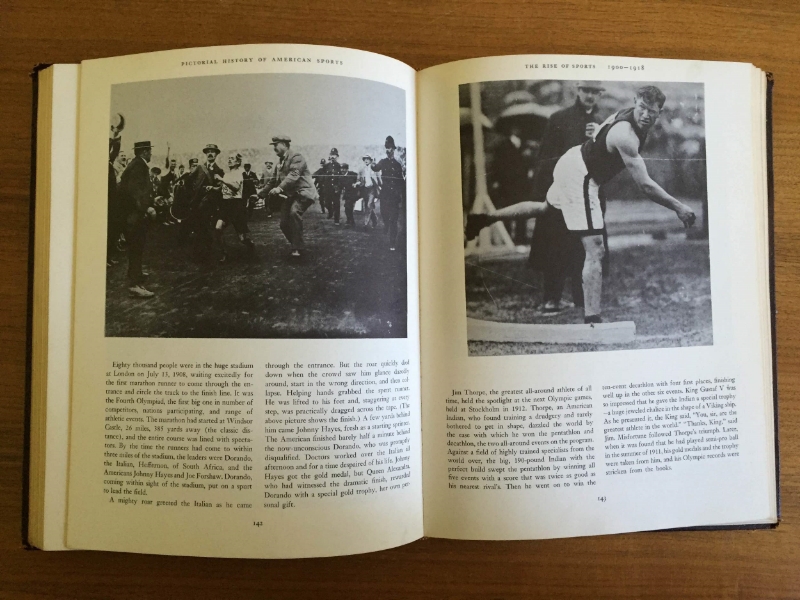

My Dad had this leather-bound book filled with sports stories from the 19th & 20th centuries. I don’t know where it came from but it was one of my favorite things in our house growing up. [ed note: After reading this my Dad told me it came from his uncle, Tom Duggan. Duggan was a radio and TV personality back in the day. After hearing Duggan was my great uncle author James Ellroy said to me "You've got some bad blood in your son!" Tom Duggan is worth checking out if you are curious.] I’m drawn to historical stories, both real and fictional, and this was filled with tales of victory and defeat. It had stories of baseball players like Ty Cobb, boxers, rowers, runners, leather helmeted football players and even track cyclists. I was drawn in by the Olympians. I reread the sections on athletes like Jesse Owens and Jim Thorpe over and over. Their backstories were as rich as their accomplishments. Jesse Owens’ four gold medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics made me feel that anything was possible, even when the odds were stacked against you.

My Dad must have had a similar interest because he knew details about some of the athletes that the book glossed over. Most of his stories were of the hardships they faced - racism, financial trouble, and the quagmire of amateur and professional athletics that plagued early Olympians. I remember peppering him with questions about how good Jim Thorpe was, and why his Olympic medals were taken away. I feel like my Dad always had an answer. The stories he told painted a vivid picture. It looked a lot like Jim Thorpe standing alone and cold in his Canton Bulldogs cape after a hard game.

Despite all of their talent many of these athletes struggled to get by. Their lives weren’t filled with lucrative contracts and happy endings. The athletes in my Dad’s book had hard lives. In the photos and drawings they look hungry and desperate. There was a longing in their eyes that I recognized. I wanted to understand what drove them. Was it money, search for glory, a form of self-expression?

“Most of his stories were of the hardships they faced - racism, financial trouble, and the quagmire of ‘amateur and professional’ athletics that plagued early Olympians.”

Their stories felt pure to me. I wonder if it was the way my Catholic ancestors felt about tales of saints and martys. There was power in these stories and I loved them for it. Their sacrifice, hardship, and victories taught me an early lesson. Life might not be fair, but it could be noble, and if not noble, certainly interesting.

My own life did not take a path I expected. At times life has felt neither fair or noble. Now I can’t even remember what my expectations were. I knew I wanted to be a writer but I ended up on a different path thanks to the advent of the internet. I wrote here and there, but mostly I put it off. I began to believe the lie I told myself, "You will get to it someday."

While pursuing a tech career in Silicon Valley I found myself confiding a story idea to a friend. It was about a women’s bike race, then called the Nature Valley Grand Prix, that took place in 2009. To me, it was one of the most dramatic and amazing races I had heard about and nobody seemed to find it that special. I wanted to tell the story to people the way I saw it.

I had only a few slim facts but I started writing. I filled in the blanks trying to imagine how the women in the race might have thought or by digging around online race reports, listservs, and outdated cycling websites. After about 30 pages I stopped. I have yet to publish it.

I told my friend about these athletes. The women in my story did not make much money. They lived the spartan lifestyle of a professional cyclist. Small houses, used furniture, basic cars, simple food... not a lifestyle for the faint of heart. They exhibited a level of dedication I found both incomprehensible and powerful. I explained to my colleague how I felt stupid for pursuing a story that wasn’t lucrative or likely to generate much interest.

[For the record, I did pitch the story to a publisher familiar with bicycle racing. While he was both polite and engaging he did not think it would sell many copies.]

“Your interest in these athletes makes sense to me,” My friend said. “They are pursuing what they love to do regardless of the cost. You relate to them.”

“The women in my story did not make much money. They lived the spartan lifestyle of a professional cyclists. Small houses, used furniture, basic cars. Healthy but mostly simple meals…a lifestyle not for the faint of heart. They exhibited a level of dedication I found both incomprehensible and powerful.”

I did feel a kinship to these people. They were willing to try, regardless of the cost, to reach for something - even if the prize at the end wasn’t very big. They wanted to be great if only to themselves.

I started following the story. I did interviews, real research, and a lot of rewriting when my made up notes didn’t make any sense. The more I spoke to the women cyclists the more they reminded me of the athletes in my Dad’s book. They felt real. None of them had million dollar contracts. They didn’t have deals with Nike. They weren’t running charitable foundations on the side to offset travel expenses, summer homes and black tie parties. Garden salad, yes; garden parties no. These athletes were some of the best in the world, and they were making it all happen with the help of meager salaries, part time jobs, and family support.

A common element emerged among the women I interviewed. Almost every single one dreamed of the Olympics. The more I heard it the more I could see the archetypes of these women in my Dad’s book. I remember my own dream of the Olympics. I think the only adventure that could have eclipsed the Olympics would have been discovering a door to Narnia. I wanted it so badly, but as I grew up I realized it would never be an option. For me, the crucial ingredients were missing– talent, skill, drive, magic–all the things that can get you there.

This story is an offshoot of that project I started in 2009. After the London 2012 Games I was curious, what does it take to go to the Olympics when life isn’t fair. Shelley Olds and Megan Guarnier had both just come off two very different kinds of Olympic defeats. Beth Newell was just starting her journey, and was filled with optimism and hope. I started keeping notes, videos, and selling bits of their stories when I could find a taker.

I want all of the women I’m writing about in this project to succeed. I want them to make it to the Olympics, to win world championships, to become famous... but they won’t. Life isn’t like that. Life isn’t fair. It isn’t filled with happy endings. Sometimes all you are left with is the story of the journey. How one continues on, after losing, is when things get interesting.

But this is a sports story. It is full of hyperbole and drama. There will be winners, and there will be losers. At the end I hope you can get a glimpse of what it means to go all in.

01 : Setbacks

01 : Setbacks

In recent weeks Megan Guarnier has become one of the most talked about American cyclists in the world. Her victories at US Road Race Nationals, the Tour of California, Philly, and the Giro Rosa have established her, not just as a top American rider, but the top rider in the world. She’s a favorite for an Olympic medal this summer but it has not been an easy road to Rio.

In one way Megan Guarnier’s selection to the 2016 Rio Olympics seems clear. She strung together an impressive series of big results starting in 2011 when she won the Giro di Toscana. In the spring of 2012 she put together a string of top 10 finishes in Europe and won her first US National Road Race Championship. In 2013 she moved to Europe to race for Rabobank, one of the top teams in the world. A year later she joined Boels-Dolmans, another top European team.

Her racing trajectory sounds logical in retrospect, but her path has been anything but straightforward.

In 2012 Guarnier’s UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale - the governing body of the sport) points helped the US earn a fourth starting spot for the women’s road race at the London Olympics. The number of riders each country can send to the Olympic road race is determined by a mix of UCI points and rankings. The exact criteria varies each Olympic cycle but to date the maximum number of riders a women’s team can send is four.

“Despite a successful European schedule leading up the Olympics, aimed at gaining the US and herself as many UCI points as possible, Guarnier was left off the squad for the London 2012 Olympics. ”

Despite a successful European schedule leading up the Olympics, aimed at gaining the US and herself as many UCI points as possible, Guarnier was left off the squad for the London 2012 Olympics. USA Cycling took Evelyn Stevens, Kristin Armstrong, Shelley Olds, and Amber Neben instead. It was devastating. Guarnier was ready to fight, and took the matter to arbitration but lost.

Nothing seemed to come easy for Guarnier. It wasn’t just the 2012 Olympic selection. She was left off of the 2011 World Championship team and then her attempt at winning the Giro di Toscana in 2012 was thwarted when a teammate took an unexpected lead and left Guarnier in a support position for several days.

Her results improved year after year moving her ever closer to the top of the sport, but there was a noticeable lack of buzz around her. There was always another rider who got the time trial bike, who was better suited for the course, who appeared on the magazine cover. Team leadership, equipment, opportunity - it never felt like resources or respect were freely given.

It is hard to say why she never became the next big thing. There are a host of possible explanations - lack of confidence, unwillingness to overstate her talent, inability to spin prior achievements into a good story, her refusal to demand rather than ask for what she wanted.

Guarnier doesn’t have a natural rapport with the media. Until recently they did not pay much attention to her. She’s active on social media, but she’s not religiously ‘gramming' crazy photos or tweeting ironic and sarcastic insights. Maybe it’s her Upstate NY/New England upbringing but Guarnier is direct. She’s not big on subtext. She doesn’t like fake. Loyalty is important to her. She keeps her small village of supporters: her husband, friends, coach, and parents, close. What she lacks in magazine covers she makes up for in die-hard supporters at each race.

In the end it worked in her favor. Instead of becoming a media star she became a bike racer. One of the best in the world.

“In the end it worked in her favor. Instead of becoming a media star she became a bike racer. One of the best in the world.”

Setbacks can make or break an athlete. Some use them as fuel, some crumble under the weight of disappointment. Guarnier’s friends call her ‘Mega’ for a reason. She doesn’t approach any element of life half-heartedly. Each obstacle she encountered in her cycling career has made her more resolute.

In 2013 when she left the US to ride for Rabobank, the home team of the world’s best cyclist Marianne Vos, Guarnier had a plan. The selection criteria for the 2016 games would not be announced until sometime in 2015. The assumption was it would be a mix of UCI points, World Championship medals, and results at key races like national championships and World Cups (now WorldTour.) Any road she took could be the wrong one.

Nothing would be left to chance on the next go around. It was time for Megan Guarnier to see just how good she could be.

02 : Opportunity

02 : Opportunity

Cycling is an odd sport. Despite a few surges in the 80’s and early 2000’s it is not a mainstream option for most kids growing up. For many it is a mode of transportation you use as a child when you can’t drive or a way to get to work after your driver's license has been suspended. Bike racing is expensive. It requires a lot of insider knowledge. It is not easy to get started. And most of all, it's hard; really hard.

If you are training correctly you are, in all likelihood, perpetually hungry, tired, in some kind of pain, and ready to hurl or collapse after a workout. On top of all the general roadblocks, women's races are historically smaller and offer far less compensation than men’s fields at every level. Despite all these barriers US women have won six Olympic medals in road disciplines, compared to men’s three, since the first women’s Olympic road race in 1984.

“In 1994, while she concurrently worked a full-time job as a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, Brems (then Kurreck) won the first Women’s World Time Trial Championship. Cycling was not Brems’ first sport. ”

I started interviewing women cyclists for articles and blog posts around 2009 and was impressed with how many of them had been elite athletes in high school or college. I’m not talking about women with athletic tendencies. These women have been enmeshed in playing sports since a young age and have participated in competitive NCAA programs that were professional in all but name. They did not start their athletic careers in cycling as did Marianne Vos (Rabbobank/NED) or Coryn Rivera (UnitedHealthcare/US), prodigies who started racing when most kids were playing soccer or swimming. They came from a wide variety of sports; volleyball, rowing, soccer, running. They had found their way to cycling through injury rehab or as a way to satisfy a need to compete.

Karen Brems was one of my first interviews. While working a full-time job as a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, Brems (then Kurreck) won the first Women’s World Time Trial Championship in 1994. Cycling was not Brems’ first sport. While attending the University of Illinois from 1980-1984 Brems had competed as a gymnast. She excelled and in 1984 was named the Illinois Athlete of the year, but she was not on the Olympic track. Brems later became one of the first women cyclists to transition to cycling from collegiate athletics in the post-Title IX world.

While Title IX has not had a direct impact on cycling, the women’s peloton has benefited from a generation of athletes whose talent and skills were developed at compliant institutions. At its core Title IX is not about sports, it is about opportunity. Specifically it is aimed at providing equal access to federally funded educational programs.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

The history, controversy, and teeth behind Title IX is worth a detailed examination on its own, and if you are interested in more detail I suggest starting with the Play Fair handbook - Play Fair: A Title IX Playbook for Victory - Women's Sports Foundation.

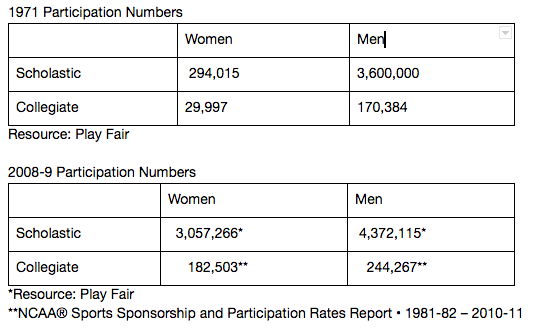

Here is a condensed version. The rules behind Title IX extend to all education programs, but athletic options for women at the high school and collegiate level were noticeable for the level of inequity. While Title IX passed in 1972, compliance did not start until the late 70s which then provided more options for women athletes. Even as enforcement began institution acceptance lagged. In the early 1980s compliance began to improve and participation numbers for women athletes rose. By 2009 participation rates were still not equal with their male counterparts but the total number of women athletes had increased dramatically.

Title IX boosted female participation in sports at the scholastic and collegiate level but where were they to go after university eligibility ended? Professional women’s sports are still in development making it difficult to dream of a career as a paid athlete. Events like the Olympics and FIFA World Cup serve as a pinnacle of achievement, and a possible avenue for generating revenue, but are primarily dependent on winning. The number of professional spots open for athletes coming out of universities is limited. A sport with a little bit of money, geographically dispersed, and a loose but growing infrastructure could go a long way. Enter bike racing.

Cycling exists in a strange netherworld in professional sports. The meaning of professional can be diced a multitude of ways. The main governing body, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), offers a 'professional' license for men but not for women. Within the men’s ranks there are several categories of professionals, everything from a WorldTour racer who commands a seven figure salary to a neo-professional making minimum wage. Some teams expect riders to bring their own sponsors and salaries, in effect, make them pay their own way. Top women's teams register with the UCI, making a UCI Women's Team the defacto 'professional' category.

“The Olympics was a big thing. Being a gymnast ever since I was a little kid I dreamed about going to the Olympics, watched it on TV and it was pretty clear pretty early that I wasn’t going to do it in gymnastics. ”

Possessing a professional license does not mean that you are able to make a living racing bicycles. A handful of women cyclists can make a decent salary but many, if not most, riders are living hand to mouth. Earning a living, or even a partial one as an athlete, requires hustle, creativity and sacrifice. Cycling, which operates on the fringe of mainstream sports, offers unending promise to those willing to give it a try. Prize money at races offers an immediate performance incentive. Existing club and team organizations offer logistical, technical and financial support. The loose format rewards talented, hungry and eager athletes. It’s a free market system with few constraints to going pro. Have you got a big set of lungs, are willing to suffer, and don’t mind the occasional broken collar bone? There is a bike race waiting for you!

Cycling went through a boom in the 80s thanks to 7-Eleven, the 1984 Olympics and Greg Lemond’s Tour de France wins. International success during this time period by pioneers like Connie Carpenter, Beth Heiden, Rebecca Twigg and Inga Thompson paved the way for the next generation of racers. Participation numbers increased and women started finding their way to the sport. In the late 80s and early 90s cycling provided a way for a handful of legendary athletes, like Laura Charameda (road racing) and Julie Furtado (first as a road racer then as a mountain biker), to compete and make a living. Women began to emerge from collegiate sports—like swimming, running, and soccer— and find their way to the races. Karen Brems was one of these athletes.

Brems graduated from Illinois and began her career as a software engineer. She moved to California and drifted into triathlons, centuries, and eventually bike racing. After college cycling helped fulfill a lifelong athletic ambition. It gave her a path to the Olympics.

“The Olympics was a big thing,” Brems said. “Being a gymnast ever since I was a little kid I dreamed about going to the Olympics, watched it on TV and it was pretty clear pretty early that I wasn't going to do it in gymnastics.

“Winning World's was a surprise to everybody, including myself, and it showed me I wasn't just making it. I wanted the medal.”

Brems’ experience would be repeated by dozens of women athletes in the coming years. Kristin Armstrong, Christine Thorburn, and Amber Neben all found their way to cycling after college, and all went on to earn World Championship medals and represent the US at the Olympics.

American cycling has been blessed by several generations of talented women looking for a home. A common thread between decades and riders is the Olympic Games. It is the marquee event for women athletes - their Tour de France, their Paris Roubaix. The Olympics is one of the few events that will draw the eyes of the entire world to their sport, but it is not without risk.

For Karen Brems, who finally made it onto the US team after her third attempt in 2000, focusing on the Olympics has a downside.

“If all you think about is the Olympics it's not enough because it's only once every four years,” Brems said. “It's so hard to make the team. There's so much that has to go right. There's politics. You have to enjoy the journey really.”

03 : NorCal Connection

03 : NorCal Connection

California was a compromise that my spouse and I found mutually acceptable. I wanted out of Canada, and she could get a job at Stanford. I had quit riding when we moved to Toronto in 1998 and started up again after we moved to California. My involvement in the large Northern California racing scene is what eventually led me to Shelley Olds, Megan Guarnier, and Beth Newell.

After the London Olympics I decided to try filming and interviewing these determined cyclists to gain insight into their drive and motivation. I made a leap that each woman would aim for the 2016 Olympics in Rio and was intrigued by their varied and idiosyncratic journeys.

While each woman’s profile has similarities they could not be more different. Shelley Olds (35) played soccer for Roanoke College and showed early promise across several cycling disciplines including road, track and cyclocross. Olds is the most at home being a professional athlete and cycling exists more as a vocation than a job for her. Beth Newell (34) ran in college and started riding as a way to get to work. Newell rose to local notoriety as a key member of the Hellyer Velodrome community with a funny, self-effacing blog, and quickly growing list of results. Megan Guarnier (31) also competed as an athlete in college until sidelined by an injury. Guarnier showed early promise as a sprinter with success on both the track and in criteriums. Her intense, steady approach to racing is reminiscent of other Bay Area Olympians like Karen Brems and Christine Thorburn.

“My involvement in the large Northern California racing scene is what eventually led me to Shelley Olds, Megan Guarnier, and Beth Newell. After the London Olympics I decided to try filming and interviewing these determined cyclists to gain insight into their drive and motivation.”

When I arrived in California I joined a local club called Alto Velo, which also supported a professional men’s team and elite/pro women’s team. The club had zero social and volunteer commitments to join so it fit me perfectly.

At the time I joined Alto Velo the top women’s rider in the club was Christine Thorburn, a former collegiate runner who was finishing up a medical degree at Stanford. Thorburn was doggedly pursuing an Olympic spot with the help of Karen Brems, her husband Ted Huang, and a host of other club members. Thorburn made the team with an emphatic victory at the US National Individual Time Trial Championship.

Several months after the 2004 Olympics Thorburn wrote an email to the club listserv about her path to the Athens games. She outlined the general plan and tactics she followed that ultimately resulted in a time trial spot in Athens. It helped that Thorburn, a self described type-A personality, did not spare any detail in her explanation. Thorburn covered a wide range of topics including her underdog status, time trial and road race tactics, bike fitting, bike testing, race selection, training strategies, selection arbitration, the psychological impact of the whole process. It was a detailed, technical process that required a team of volunteers across the country.

Her selection was not without controversy. Kristin Armstrong, who had been racing strongly in Europe, was also in contention for one of two time trial spots, but the position was awarded to Thorburn who had won the US ITT Championship. Armstrong contested the discretionary selection based on her interpretation of the selection criteria. The arbitration was set for several days ahead of the road race in Athens. Armstrong ultimately dropped the case, ceding the spot to Thorburn who finished fourth in the Olympic time trial, 20 seconds out of third place.

Thorburn retired, but Armstrong continued racing. The experience deeply affected Armstrong, and she would never again leaver her team selection in doubt. Armstrong went on to qualify for both the Beijing and London Olympics winning two consecutive gold medals.

I started to write for NorCal Cycling News (NCCN) in 2008 and focused primarily on riders living and racing in the Bay area. The area was, and still is, a cycling Mecca with dozens of group rides and thousands of cyclists. The area was rich with talent and teams. It is the home of industry giants like Specialized, Bell, Giro, Fox, Santa Cruz Bikes, Ritchey and Strava. Access to races, equipment and coaching made it easier for riders like Brems and Thorburn to cultivate their talent. New riders were coming out of NorCal every year, and a handful were becoming dominant figures nationally, and internationally.

I had covered Megan Guarnier, Shelley Olds, and Beth Newell on the local circuit for NCCN. None were California natives but all three had competed in collegiate sports programs, and later moved to California for work and personal reasons. Each one had taken up cycling for very different reasons but quickly found that their talent could take them beyond the local racing scene. By 2012 Guarnier and Olds were both on the short team for the Olympics, and Beth Newell had won her first track national championship.

“By 2012 Guarnier and Olds were both on the short team for the Olympics, and Beth Newell had won her first track national championship.”

I had always felt that Northern California was like an independent country when it came to cycling. Only a handful of places in the country could crank out the same level of talent as Northern California. The depth and variety of talent from my adopted home produced some of the best cyclists in the world. I had ridden with Guarnier, Olds, and Newell either on group rides or in races at Hellyer Velodrome in San Jose, CA. By sheer proximity I was able to get a view of their personalities that made their success both obvious, and sometimes surprising.

Not often is one able to get to know an athlete as they discover their own talent. I was never close in ability to any of these women but I was afforded an opportunity to see how they trained, lived and raced. I can still visualize Guarnier climbing up Tunitas Creek road, Olds bridging an attack at Hellyer, or Newell watching for a move during a points race. This wasn’t like watching Michael Jordan or Venus Williams from a distance. Cycling's intimacy and ability to share experiences binds the sports stars with the tifosi in a unique way.

The first thing I noticed about Guarnier when I rode with her several years ago was her laugh. It was generous, deep, and loud. To this day I think of it as “booming.” She applied it to her self conscious reflections on her own behavior as well as random jokes from those on the ride. It was offset by her ability to quickly shift gears when asked a serious question. Guarnier likes direct questions and clarity. Ambiguity does not suit her.

The way she’d focus in on a question reminded me of an eagle I once saw in an urban setting. It seemed nervous sitting at the top of a pole or building on El Camino Real in Menlo Park, CA. I wanted a closer look and as I got closer I realized it was watching a pigeon it had brought down. I crossed some invisible barrier and all of a sudden the bird fixed me with an attentive stare. The eagle's vigilance was the tightly wound bearing of a predator. It changed gears in and out of focus so quickly that the shift in focus itself what was most disturbing.

“So I had to make the tough decision to retire from swimming when that was my identity. I was a swimmer. For as long as I could remember I was a swimmer, and to take that part of my identity away was challenging. But it did open new doors for me.”

Guarnier dreamed of going to the Olympics as a child first as a skier and then as a swimmer. She excelled in the pool and swam competitively first in high school and then at college. She swam for 13 years but while attending Middlebury College in Vermont the increasing demands of swim workouts and injury rehabilitation began to take a toll on her academic goals.

“At one point I had to take a step back and say ‘Look, I’m not at college to swim, I’m at college to get an education.’” Guarnier said. “So I had to make the tough decision to retire from swimming when that was my identity. I was a swimmer. For as long as I could remember I was a swimmer, and to take that part of my identity away was challenging. But it did open new doors for me."

Megan Guarnier discusses her background and cycling at the 2013 US National Championships

With swimming behind her, but her desire to compete intact, Guarnier decided to pursue triathlons. She started a new training program and eventually a friend in her dorm at Middlebury encouraged her to attend to a bike race.

“I went to a bike race and I never really looked back at triathlons,” Guarnier said. She had found a new path.

Guarnier began to pursue it after she graduated while she worked a day job at an engineering firm in Northern California crunching numbers while working in probabilistic risk assessment.

Other athletes graduate from college and then drift into cycling as a way to fuel their competitive spirit. Professional athletic opportunities after college are rare for women and usually not lucrative. Shelley Olds graduated from Roanoke College, where she had been captain of the soccer team, and struggled with what was next. Olds began to work a series of entry level jobs, first as a physical therapy aide and then in an administrative position at Kaiser, but the 9-5 grind never felt right.

"When I started working full time when I got out of college, I knew that I wasn't doing what I was meant to do,” Olds said. "I knew when I finished soccer that it was a really low point for me. I kind of was lost, ‘What am I going to do; I need [athletics] back in my life.’

“Luckily I found cycling which is better than I ever could imagine as far as sport goes because it's so dynamic and you can be so versatile. I know I'm athlete at heart. That's what drives me and that's why I'm happy every day now because I'm doing what I love to do."

Olds started riding in 2005 and, at the urging of a friend, took out a racing license. She excelled at a variety of disciplines; cyclocross, road and the track. Olds began to focus on track racing and by 2008 was competing at UCI World Cups around the globe. Olds began to seriously pursue an Olympic track spot with the help of Nicola Cranmer, the founder of the Proman Cycling team - an early incarnation of the current UCI program Twenty16-Ridebiker Alliance.

Olds specialized in the points race, a tactical mass start event that requires speed, endurance and a gambler's winning instinct. She possessed the speed and innate sense of how to read a race.

I raced against Olds at Hellyer Velodrome where she would enter the men’s races while preparing for the World Cup circuit. She was quick, focused and possessed a finely honed race sense. I am not a particularly strong rider, so I try to learn by following riders who can read the ebb and flow of a race. They are the riders that are always in the right move, use a small amount of energy to make a big impact, and always have a result. I remember watching her and thinking, ‘If I want to learn how to race, this is a rider to follow.’ She wasn’t overwhelming the field with her power or speed. Her talent was instinctive vs. obvious. She was like a shark - dominant, yet unseen and invisible until she attacked.

“The Olympics has always been the backdrop for everything for me,” Olds said. “It’s the ultimate thing for an athlete to do and especially in cycling as it is now”

Olds appeared to be on schedule for the Olympics after winning several national track championships and World Cup medals. Then the UCI changed the Olympic track format, removing the points race, and leaving only the Pursuit and Omnium available for women endurance riders. Olds saw the writing on the wall and switched to full-time road racing.

Her road career was just as successful. She racked up several big domestic wins and in 2012 won the Tour of Chongming Island World Cup. The win helped earn her a spot on the 2012 London Olympic team where she finished 7th in the road race after flatting out of the winning breakaway.

Olds had made the Olympic team. She had been in contention for a medal. For some people these achievements might be enough but not for Olds. To be so close and miss can be worse than not being there at all, especially for an athlete as competitive as Olds. Can any athlete that is talented and driven enough to make it to the Olympics have a reasonable view of achievement or does the bar of success just continue to rise in a never-ending ladder?

“The Olympics has always been the backdrop for everything for me,” Olds said. “It's the ultimate thing for an athlete to do and especially in cycling as it is now.”

Like Olds, Beth (Newell) Hernandez is also a product of Hellyer Velodrome. In some ways she is the most unlikely of the three women to be an Olympic candidate. Newell ran track and cross country in college, but was focused on her career when she moved to the Bay area with AmeriCorps in 2005. Newell did not start riding to rehab and injury or fuel an unquenched competitive fire. She started riding as a way to get to work. At first, cycling meant transportation and not sport.

The story of her first bike is legendary. After moving to California for her AmeriCorps job Newell’s car died unexpectedly. The 22 year old college grad was low on money and needed to get to work. She put her Midwestern can-do attitude to work and scrounged an abandoned bike out of a dumpster. Newell hadn’t learned to ride a bike as a child so she quickly taught herself, gave up on the car, and started riding to work every day. The story was immortalized in the East Bay Express.

Newell began to ride more with different groups in the East Bay and eventually found her way to Hellyer Velodrome where she began her racing career. She wrote about her racing exploits in a blog, covering the culture and aesthetics of racing in a velodrome as if she were a self effacing anthropologist. Her opening to a post about discovering chamois cream succinctly conveys the confusion and horror that can be involved in getting started racing.

“Well, when we were biking home one morning Fred says something along the lines of: ‘Bethie, so we need to talk about hygiene. So, if you don’t keep yourself clean you can get these sores. and in my day I didn’t have a doctor so I’d lacerate them with a knife.’ I couldn’t really tell you what was more weird... have a 65-year-old talk to me about sores in my personal area.... or the lacerating things with a knife part...but moreover, i really didn’t understand what the hell he was talking about. it was kind of like the sex talk my mom gave me.”

The blog was funny, direct, insightful, and filled with humility. It masked her potential as a rider and which progressively became more obvious. She made national news in 2011 after winning the Omnium and Points US National Championship races. Her achievements did not get her on the short list of contenders for a spot at the 2012 London Olympics but it did land her a job on the Now-Novartis professional cycling team.

The blog posts slowed down and Newell's focus on racing increased. Then, in 2013, she medaled on the track at both the Pan-American Championships and the Manchester World Cup. Newell’s journey towards a possible Olympic spot was just getting started.

There are few ties between these riders. Guarnier, Olds and Newell know each other in passing. Their racing styles and skills are drastically different. Olds now lives in Spain, Guarnier spends her time traveling between Europe, New York, and California, while Newell is still in Oakland. Their connection to Northern California loosely binds them together but I see a similarity in their re-invention as cyclists and athletic ambitions. They each found something new in cycling, something they didn’t have before, and used it to follow a dream.

I was always aware that being a professional woman athlete required talent, sacrifice and compromise. Three years into this project I began to see that making it to the Olympics would require an additional level of commitment and luck. It required everything a person could give physically, mentally, and emotionally. It required a leap of faith I cannot even begin to describe. Watching the process unfold has been both exciting and painful...and we have yet to reach Rio.

04 : #1

Megan Guarnier does not have an actual ‘Olympic dream.’ When she dreams of bike racing it is a classic anxiety dream. She’s at the start line and doesn’t have her shoes, or the other one where she misses the start and has to ride through the race caravan to catch the peloton. It’s not a big sweeping dream where she’s winning gold or getting cut from the team. They are dreams of details overlooked and procedures gone wrong. The dreams keep her vigilant. They highlight how Guarnier must never let her attention drift far from the puzzle in front of her.

04 : #1

Megan Guarnier does not have an actual ‘Olympic dream.’ When she dreams of bike racing it is a classic anxiety dream. She’s at the start line and doesn’t have her shoes, or the other one where she misses the start and has to ride through the race caravan to catch the peloton. It’s not a big sweeping dream where she’s winning gold or getting cut from the team. They are dreams of details overlooked and procedures gone wrong. The dreams keep her vigilant. They highlight how Guarnier must never let her attention drift far from the puzzle in front of her.

Megan Guarnier does not have an actual ‘Olympic dream.’ When she dreams of bike racing it is a classic anxiety dream. She’s at the start line and doesn’t have her shoes, or the other one where she misses the start and has to ride through the race caravan to catch the peloton. It’s not a big sweeping dream where she’s winning gold or getting cut from the team. They are dreams of details overlooked and procedures gone wrong. The dreams keep her vigilant. They highlight how Guarnier must never let her attention drift far from the puzzle in front of her.

2011 Key Stats

- UCI Rider Ranking 34

- UCI Team Ranking 12 (TIBCO - To the Top)

2012 Key Stats

- UCI Rider Ranking 36

- UCI Team Ranking 13 (TIBCO - To the Top)

- UCI Team Ranking 1 (Rabobank)

After being left off the London squad Guarnier had three years to figure out how to get a ticket to the Rio Olympics. Why only three years? The Olympic selection process is a difficult equation that starts with getting named to the USA Cycling’s Olympic long team. The long team is a pool of riders, between 10-15 women, from which the final roster for the Olympics will be comprised. Elements in consideration include performances at nationals, UCI race results, and overall UCI rankings.

Oh, and if you medal at World Championships then you pretty much get an automatic qualification. If a rider does not get a medal at Worlds then they need to fight for a discretionary spot. Nobody wants that. It means one’s Olympic fate is left to a selection committee. Nothing good ever came out of a meeting so the best solution is to try and remove all doubt out of the equation.

Three years to get this right. Where do you start?

Step 1: Move where the points are (2013)

UCI points are important. They determine the UCI rankings for both individual riders and teams. They determine race invites, they impact a country's roster size for events like World Championships and the Olympics, and they can impact how much a rider is paid. Everybody; teams, riders, and national federations all want more UCI points.

In 2013 roughly 75% of the major races on the calendar were in Europe that included the following:

- 7 out of 8 World Cups

- 21 out of 27 one day races categorized as 1.1 or 1.2

- 18 out of 24 categorized stage races

The obvious solution if you want to collect UCI points, and go to Rio, is to move to Europe. So Guarnier makes the logical decision and moves to Europe.

Guarnier takes on a contract with Rabobank, and moves with her husband to Sittard, Netherlands. It is not an easy decision. Guarnier is close with her family and friends in the US. To help facilitate the move her husband Billy Crane gives up a Silicon Valley technology job for a position organizing part of USA Cycling’s Junior program in Europe. Living in Europe may sound idyllic, but grey weather and the cultural differences of daily life are a far cry from the Parisian museums and hills of Tuscany that most people dream about.

But the team! The team is the best in the world. Rabobank is home to Marianne Vos, perhaps the best most versatile cyclist in the history of the sport. Under Vos’ leadership Rabobank finished 2012 as the number one ranked team in the UCI standings. And therein lies the catch. On Rabobank you are working for Vos.

Midway through 2013 Guarnier reflected on her time working for Vos.

2013 Key Stats

- Guarnier joins Rabobank

- 2nd Omloop Het Nieuwsblad

- 9th Drentse 8 van Dwingeloo

- 7th Emakumeen Euskal Bira

- 2nd Trophée d'Or Féminin Stage 5 RR

- 9th GC Boels Ladies Tour

- 3rd Stage 2 ITT

UCI Rankings

- UCI Rider Ranking 52

- UCI Team Ranking 2 (Rabobank)

- UCI Team Ranking 11 (Boels)

“I hope I'm contributing, Sometimes I wonder if she should just do all this on her own,” Guarnier said laughing. “This year I've seen that even the best need teammates, and I came onto the team knowing I wanted to be the best teammate I could possibly be. And riding for, arguably, the best team in the world, I need to be the best teammate in the world. It makes me take my domestique game up another level.”

Despite limited opportunities to ride for herself, Guarnier put in several strong performances and a quick view of her results reveals a season filled with top 10 and top 20 finishes. Vos on the other hand won over a dozen races, including five UCI World Cups and the overall World Cup title.

Step 2: Find the Magic(2014)

Not everybody is made to be a leader. There is a lot of pressure that goes along with the responsibility. Many riders prefer to work behind the scenes in support of a team leaders, while some accept the role hoping to one day graduate to the top position. Guarnier definitely wanted to be a leader. She had respect for the system that rewarded domestiques by eventually moving them into leaderships positions, but Vos was two years younger than Guarnier and not going anywhere. Guarnier had proved she was willing to ride in a support role and win big races. So she left for greener pastures where both facets of her ethos could be utilized.

The following year Guarnier made the jump to Boels-Dolmans which had finished the 2013 season ranked 11th in the UCI standings. Boels was a strong Dutch squad, but played second fiddle to Rabobank. It was a small step down in terms of prestige but the Boels’ roster had a lot of potential. The line-up included several big names like Lizzie Armitstead and Ellen van Dijk, and offered opportunity to free Guarnier up to ride for herself.

2014 Key Stats

- Guarnier joins Boels-Dolmans

- 7th Cholet Pays de Loire Dames

- 8th Ronde van Vlaanderen

- 9th GC Festival Luxembourgeois

- 3rd Panamerican Championship Individual Time Trial

- 2nd Panamerican Championship Road Race

- 6th US National Championships ITT

- 2nd US National Championships Road Race

- 6th GC Emakumeen Euskal Bira

- 7th GC Giro d'Italia Internazionale Femminile

- 5th GC BeNe Ladies Tour

- 10th GC Boels Rental Ladies Tour

UCI Rankings

- UCI Rider Ranking 26

- UCI Team Ranking 3 (Boels)

The team suited her. In a 2015 video interview Guarnier tried to describe the profound effect of finding a team she felt at peace with.

“It was better than I ever could have imagined,” Guarnier said “The team Danny [Danny Stamm - Team Director] put together was incredible. On and off the bike we were a real team, and it spoke for itself in the results starting at the Drenthe World Cup.

“The chemistry within the team was really important. It always is, and you always say that but then once you find that niche, and find that chemistry you are are like ‘Wow, there is nothing like this.’ I’ve never experienced this on a team. I didn’t know it existed.”

Guarnier found camaraderie and harmony on Boels-Dolmans, where her teammates nicknamed her after a cartoon bird ‘Calimero.’ While she didn’t achieve the results she would have liked the team’s results and the atmosphere made up for it. Despite a lack of wins Guarnier’s results were still notable. She rode herself onto the podium at both the Pan-American Championship road race and time trial. She placed second at US National Championship road race and grabbed several top 10 general classification finishes. Guarnier moved up to 26th in the UCI Rankings. Things were coming together.

Step 3: Learning the Art of Winning (2015)

Cycling is a cruel sport. Riders can thank their team till the cows come home but only one person gets the credit. A director will sometimes pop up and get credit for their tactical brilliance but their contribution is inevitably lost to history. Sure there is a team classification, but let’s be honest - it’s a third tier consolation prize. This is an individualists sport. If you want to earn glory in cycling that means you need to learn to be hard. You will need to drain your team of every resource they can provide, you must use your teammates like pack animals until they collapse, and it is necessary befriend enemies and betray teammates to cross the finish line first.

The fact is, unless you are a complete narcissist, one must work hard to learn the art of winning. Some riders, like Marianne Vos, learn to win at an early age so when they hit the full height of their power they are primed and ready to go. Other riders need to take the process in steps. They can get stuck in an endless rut of finishing just off the podium in 2nd, 3rd, or 4th place, never quite able to close the gap to the top step. It is a game of chance, strategy, and talent. Guarnier had proved she could win - but some saw her victories at Nationals and Toscana like blips on a radar. Her understated nature meant she wasn’t demanding attention from the federation or media. Guarnier needed to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt these performances were replicable.

The big win, the one that set events in motion, was at the Strade Bianche. It was a new event, and while it didn’t have World Cup status it had gravitas. The race, started in 2007 for the men’s field, was an instant classic with its 57 km of white dirt roads and a picturesque finish in Siena. Guarnier’s loyalty was rewarded when her team’s tactics enabled her to ride away from her breakaway companions, teammate Lizzie Armitstead and Elisa Longo Borghini, to win the first edition.

It felt big. It was an emphatic win at a one day classic. All the big kids were there and Guarnier was the best.

2015 Key Stats

- 2nd GC Women's Tour of New Zealand

- 9th Le Samyn des Dames

- 1st Strade Bianche

- 3rd La Flèche Wallonne Féminine

- 1st US National Championships Road Race

- 3rd GC Euskal Emakumeen Bira

- 3rd GC Giro d'Italia Internazionale Femminile

- 1st GC Ladies tour of Norway

- 6th Boels Rental Ladies Tour

- 3rd World Championships Road Race

Stage wins

- 1st Stage 1 Euskal

- 1st Stage 2 Giro

- 1st Stage 1 Norway

UCI Rankings

- UCI Rider Ranking 8th

- UCI Team Ranking 2 (Boels)

Somewhere out on the roads of Tuscany Guarnier crossed a threshold. Her riding was confident but you can see the fear and hunger etched in her face when you look at the highlights from Strade Bianche. Something had changed, things had finally come together.

Performance improvements are not linear. An athlete can be going along, business as usual, following the same plan they have for years and things just click for them. Their bearing changes, their confidence increases. They attack their training, diet, and race preparation with a beginner’s intensity but with the knowledge of an old soul.

After a 3rd place finish at La Flèche Wallonne Guarnier returned to the US to race the Tour of California Invitational Time Trial and US Pro Road Nationals in Chattanooga. Boels Dolmans had not sent a team to the inaugural women’s stage race at the Amgen Tour of California but Guarnier and teammate Evelyn Stevens had scored invites to the invitational time trial.

California was a Tim Gunn style 'make it work' situation. Left without much in the way of support Guarnier pulled together a last minute crew led by friend James Mattis. Mattis had ridden professionally for Webcor in the early 2000’s while working as an engineer in Silicon Valley, and knew his way around big races. He took time off of work to come to LA to help Guarnier ride the race.

The race didn’t go well. Guarnier slipped coming out of the start house and then finished an uninspiring 10th place. After the race she seemed annoyed and was already looking towards Chattanooga the following week.

“Road racing is my thing,” she told me. “That is where my focus is.”

In Chattanooga Guarnier and Stevens were up against two strong teams, UnitedHealthcare and Twenty16-ShoAir. The early race tempo was set by Kristin Armstrong and Twenty16, but on the final lap Stevens set a hard pace up Lookout Mountain. By the time leaders hit the final circuits only Guarnier, Amber Neben, Tayler Wiles and Coryn Rivera could stay in contact. Stevens attacked enabling Guarnier to sit in for the final lap.

I recall listening to other journalists before the start of the final circuits. They were all making their pick. They were looking at Stevens, Wiles and Rivera to take the win. I was surprised I was the only one picking Guarnier. She could climb, she could sprint, she could hammer for a long time and then do it over again. As if according to a script Guarnier continued to remain just outside people’s consciousness.

“I kind of fly under the radar, I totally fly under the radar,” Guarnier said about her relationship to the media. “I don’t mind talking to the media. I think there are a lot of incredible women’s stories out there and we hear one or two of them occasionally, but I think the media gets stuck in their little rut of who they want to talk to.”

Coming into the final corner first Guarnier sprinted to the line head to head with Rivera. When she crossed she didn’t know if she had won. I was the first person she saw and she looked at me yelling “DID I WIN? DID I WIN?” I was relieved with her husband Billy Crane sprinted over from the team car and told her she won. She jumped into his arms in a combination of happiness and relief.

The results began piling up, 3rd at the Giro, 1st at the Tour of Norway, and then the big one… a bronze medal at the World Championship Road Race in Richmond. After the race Guarnier was unwilling to let her finish 3rd place finish stand as a satisfactory result.

“I was happy with my result because the Americans got a podium for the first time in 21 years which was a big goal,” Guarnier said. “But, when you look back it’s a little bittersweet. Of course I would liked to have won and in the future that’s what I’m going for, is the win. I just need to have the confidence to say that and do that.

“I think being a little bit more aggressive, but it’s having the confidence to be aggressive too and not be so reactive.”

Guarnier had the hunger now. She had learned to win and she wanted them. All of them.

The most important benefit of her bronze at Worlds was it automatically qualified her for the US Olympic team. Guarnier was going to Rio. It was done. She was in. Now it was time to rule the world.

Step 4: Rule the World

It is hard to underestimate the importance of an early qualification. For starters it removes the pressure of dealing with the arbitrary nature of the selection committee. It also allows a rider to focus. Instead of trying to accumulate results leading up to the final selection, a rider can target races that will help them perform in Rio. Other than Guarnier the remainder of the team would need to fight it out in the spring to obtain the three remaining discretionary picks.

But there is a rub with an automatic qualification. It is not really automatic.

"With her bronze medal result at the 2015 UCI Road World Championships, Megan Guarnier secured a nomination to the women’s road-race squad, provided she continues to demonstrate the ability to perform at a similar level in 2016 based on results from major international competitions. “ ~ Olympic Selection Criteria Primer Distributed by USA Cycling in Spring 2016

It makes sense. A rider could qualify and then get injured, have a bad year or decide the hard work was behind them and decide to take it easy. That is not Megan Guarnier. Her drive, a stubbornness that pushes her to never quit, would not allow that.

“You have to be willing to make big sacrifices, you have to be willing to not be comfortable,” Guarnier said about getting to the Olympics. “That is a huge other aspect of it, always pushing your comfort zone.

“It’s not comfortable living in Europe, I’ll go out on a limb and say it is not fun at all. It’s an adventure, and it’s hard, and it teaches you a lot about yourself, and I wouldn’t be where I am without those challenges. But it is not always fun, it is not always roses. And that is just the living aspect of it, you have to train on top of it, and stay focused, and stay focused on your goals.”

Nothing was overlooked and come spring, Guarnier was ready.

2016 (Spring) Key Stats

- 6th Strade Bianche (1.WWT)

- 2nd Trofeo Alfredo Binda - Comune di Cittiglio (1.WWT)

- 2nd Pajot Hills Classic (1.2)

- 4th Ronde van Vlaanderen / Tour des Flandres (1.WWT)

- 1st Durango-Durango Emakumeen Saria (1.2)

- 2nd GC Euskal Emakumeen XXIX Bira (2.1)

Stages

- 2nd stage 2 Euskal Emakumeen XXIX Bira

- 1st stage 4 Euskal Emakumeen XXIX Bira

Guarnier charged into her spring season and her form was only overshadowed by her team’s historic winning streak. Boels-Dolmans won five out of seven Women’s WorldTour races that spring, a feat akin to the winning streaks of sports dynasties in basketball and football.

After a strong spring campaign Guarnier returned to the US. For the second year in a row the Tour of California was putting on a women’s stage race, the ‘Amgen Breakaway From Heart Disease Women's Race Empowered by SRAM.’ Despite the challenging title the race was on the Women’s WorldTour calendar and drew the biggest teams in the world. Top European and American riders including Marianne Vos (NED), Emma Johansson (SWE), Lisa Brennauer (GER), Kristin Armstrong (USA), Evelyn Stevens (USA), and Mara Abbott (USA) were all in attendance.

Race organizers brought most of the big names including Vos, Stevens, Armstrong, and Johansson to the pre-race press conference. Guarnier was noticeably absent.

“Odd," I thought. "I guess Stevens is the leader for this race."

The next day I tried to get a pre-race quote from Guarnier. She was wound up and having an issue with her bike so she apologized and scooted away abruptly. Curt, tense, factual - she seemed dialed in. The race was uneventful. Boels-Dolmans did most of the work to bring back a four minute breakaway, leaving the race to the final three kilometers up two sharp climbs, which at altitude would be painful.

On the final climb Stevens attacked followed by Emma Johansson. Guarnier jumped over the top of both of them and soloed in for the win. As she approached the finish I saw Guarnier check over her shoulder and smile, she looked surprised at her gap. After four days of racing Guarnier went on to take the overall win and the points leaders jersey. It also made her the Women’s WorldTour leader, not quite number one in the world but close.

And then it happened, Guarnier hit a hot streak.

A week later Guarnier won US National Championships in Winston Salem. The next week she won the Philadelphia International Cycling Classic. A month later she won the Giro d'Italia Internazionale Femminile, the biggest women’s stage race in the world. She wasn’t just the leader of the Women’s WorldTour she was at the top of the UCI points standings. She was undisputed #1 rider in the world.

“I’m just doing what I always do. I’m always trying to be better. I’m always putting in the hard work,” Guarnier said after winning Nationals. "The results may be better than they used to be, but I’m still the same Megan. I’m still the same Calimero. I’m just out there doing my job and loving what I do.”

Being number one in the world isn’t a goal, it just happens. Once you are there the fragility of the position becomes all too apparent. Anything can take you down, a cold, a bad race, a fall, age. But here she was. After years of trying Guarnier wasn’t just going to the Olympics; she was heading in as a favorite where she’ll face off against her old teammate Marianne Vos and current teammate, and World Champion, Lizzie Armitstead.

Time to check world domination of the checklist and head to Rio.

I wonder what an Olympian dreams before their big race…

Coming Soon

Coming Soon

What's next...

This project is organic so I'm always changing my mind which sections of video, supporting articles, and audio I want to layer in next. One challenge is that the 'live' element keeps changing priority. Here is the basic outline and target release dates.

- Release 1: Introduction (July)

- Is the first four "Chapters. Basically it introduces the premise of the project, the athletes and some background

- Release 2: Mega & The Selection (July)

- I started filming Megan Guarnier in 2013 and was able to catch up with her as her success grew. I also spoke with each athlete about the selection criteria. These sections will likely be mostly video, and I plan to lay out my own thoughts on the current selection process. I'm shooting for end of July. Fingers crossed:)

- Release 3: The Queen Stage & Shelley Olds (August)

- This part of the story is a bit of a tangent. I first interviewed Shelley Olds for a story I was working on in 2009. The race and its participants blew me away and changed the way I saw cycling. This will probably be mostly long form article with one or two short podcast/radio spots.

- Release 4: The Olympic Journey and Beth Newell Hernandez (August/Sept)

- BNH was always an outside shot to make the Olympics but she came so close. I'm not sure she always enjoyed the journey but sometimes we only can appreciate our accomplishments with hindsight. This will be a mix of video and written content.

- Release 5: Short Documentary (Fall)

- Once the four sections are out I hope to consolidate the interviews into a short 15-20 minute documentary which I'll make available on Vimeo & YouTube.

So.. that's the plan, which brings to mind a quote I saw at a museum in Normandy recently.

“I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”